Introduction

Following an era where the PSX reigned supreme, the 6th console generation got a significant hardware upgrade with more storage space, larger resolutions, higher poly counts, etc. The extra horsepower allowed for many genres to better realize their settings and mechanics, and JRPGs were no exception.

Real-time combat was no longer limited to the Tales and Star Ocean series, and freeform movement opened the door for various new action-RPGs like the massively successful Kingdom Hearts.

Turn-based party-battlers were still plentiful, but it was perhaps the first step to catering for a broader audience at the cost of alienating older fans.

It was also when JRPGs lost me.

The higher fidelity presentation meant that previous abstractions were now shown in their full glory, or lack thereof. Instead of a pixelated knight bowing his head and saying a single dubiously-translated line of dialogue, the protagonist was now an emotional teenager — complete with grating voice acting and a smirking portrait — blathering on for entire paragraphs with rarely an option to skip ahead.

There were no longer any blanks to fill, and the added content was skewed for a younger demographic. Consequently I didn’t play any of these games upon release, and about half of them were brand new to me.

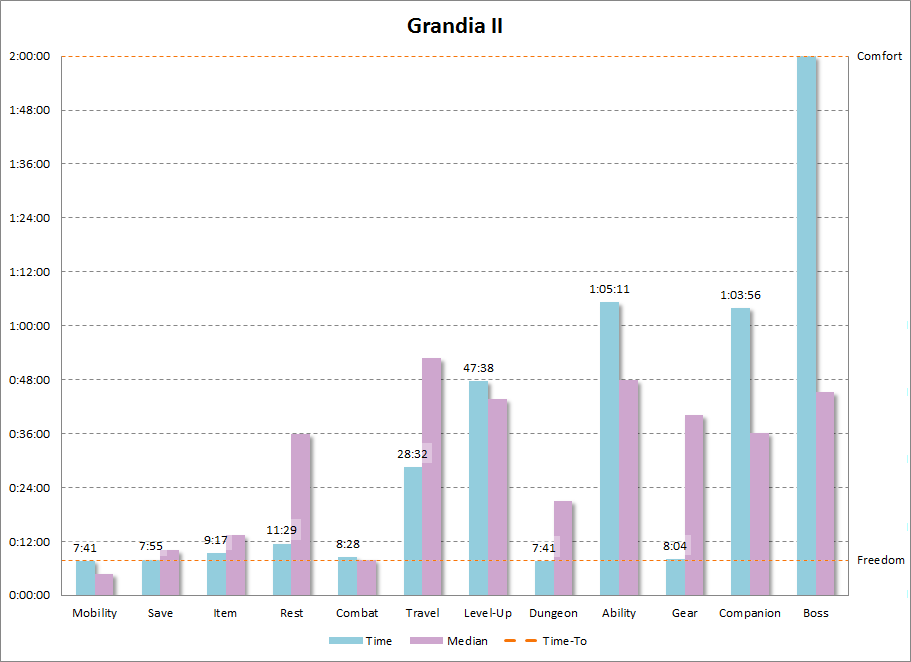

Grandia II – August 3, 2000

The Dreamcast was something of a stopgap before the PS2, Xbox, and GameCube truly ushered in the new console generation. The first of its standout JRPGs was Grandia II, the most fondly remembered entry in the series that received multiple re-releases over the years.

The opening of Grandia II smacks of the previous generation. It starts with a short anime video, followed by an in-engine cutscene involving various characters, and is capped off with another in-game cutscene introducing the protagonist.

Despite showing some combat encounters, this opening is entirely non-interactive and unskippable. However, as soon as it’s finished the milestones come rapidly.

The opening area is a mini-dungeon, with a save point close-by. Combat is initiated via on-screen enemies that glow red when they spot the player.

After the initial encounter, the first gear upgrade is obtained, followed by the first consumable, and finally a rest spot. All of this takes less than 5 minutes, and the overworld map is reached within half an hour.

From there, things slow down a bit as the first town is reached. NPCs often have different things to say when they’re spoken to repeatedly, and the plot necessitates some dungeon exploration. A level up takes place during this quest, and the first companion joins upon returning.

Ability customization follows right after, but 2 hours proves not quite enough time to reach the first boss.

FTC: NA

Miscellaneous Points:

- The protagonist starts at level 10, which is somewhat appropriate given that he’s supposed to be a bit of a grizzled veteran.

- There’s no walking around on the overworld map. Instead, all possible destinations are shown as nodes and travel happens instantly.

- Unlike other JRPGs, shops in Grandia II are all condensed into a single building that sells weapons, armour, and consumables. These shops also offer regional selections unique to their location.

- Lots of little elements in the environment jostle around as the player bumps into them, e.g., bottles, coat racks, etc.

- Perhaps Grandia II’s biggest claim to fame is its battle system that revolves around a horizontal timeline where all combatants are represented by icons. This bar is notched by two trigger points, COM and ACT, and all the icons on it continuously travel from left to right. When an icon reaches the ACT portion an action is initiated, and it executes upon reaching the end of the bar. At this point, the turn is finished and the icon is sent back all the way to the left. However, if a combatant is hit with a “Critical” attack — one of the two base attack options — they’re also sent back on the bar, delaying their actions. This delay is significantly larger when targets are already in their ACT phase, allowing players to strategically target enemies to minimize incoming attacks.

-

- Combo attacks do more damage, but they don’t delay enemy attacks.

- A “Counter” is performed whenever a character is hit with an attack, but then follows up with their own queued “Critical” strike before the original attacker’s icon has traveled back to the COM portion.

- Both Critical and Combo attacks refill an SP meter that’s used to fuel special abilities. Executing these tends to pause the battle while they play some fancy animations.

- While characters can dodge by selecting adjacent nodes, there’s no manual movement creating location-fuzziness. As the combatants run around on the battlefield, their actions take different amounts of time to execute. This makes the timeline tricky to predict, and in some cases characters will take circuitous paths to their targets resulting in the whole turn being lost.

Skies of Arcadia – October 5, 2000

Just a couple of months after Grandia II, the Dreamcast got its other landmark JRPG: Skies of Arcadia. While it was critically acclaimed for its lighthearted, adventurous spirit, it didn’t sell as well as expected. The game only got a GameCube upgrade, with various other re-releases being cancelled.

Despite this, Skies of Arcadia is fondly remembered as a title that hearkens back to what made JRPGs great in the previous generations.

After a short, in-engine cinematic, the player is thrust directly into combat. When the battle ends, the party finds itself in a dungeon with an item close by. With a bit of exploration and fighting, the first level up is achieved just before finding a save point. Within 10 minutes of the initial combat, the dungeon’s boss is encountered, and a new ability is obtained after his defeat.

When the party escapes to the overworld, the rapid pace slows down a little. This is the first time any tutorials are presented, and the player gets to explore the land aboard their airship.

Back in the protagonist’s home town, some shops open up and plenty of cutscenes and general exploration takes place. Due to the scripted nature of this segment, there actually is no manual resting until the second dungeon is completed.

Combat is initiated with random battles, which aren’t as frequent as many online complaints indicate, but they’re not rare either. Consequently the 2 hour mark elapses just before the first new party member joins the crew.

FTC: NA

Miscellaneous Points:

- In combat, each character can imbue their weapon with any of the collected elements. This is done with a simple button press instead of going into a menu and doesn’t waste the turn, ensuring the player can always exploit the enemy’s weakness.

- The party shares a segmented SP bar that fuels the execution of various spells and special abilities. The bar fills in every round, or when using a Focus option, and all abilities drain it by a different amount. In addition to using the SP bar, each casting of magic also drains the character’s MP counter by 1.

- Both the party members and the enemies move around the 3D battlefield like in Grandia II, but range doesn’t seem to play a factor in combat. A nice touch of this presentation is that during each character’s turn, the other combatants can be seen taking swings at each other. These are purely visual and never cause damage, but add a sense of dynamism to the turn-based combat.

- Lots of different objects can be investigated to provide flavour text. This works much like it did in Phantasy Star IV, the team’s previous game.

- In addition to random combat encounters, piloting the airship can lead the player to meet merchants, NPCs, or schools of (collectible) fish.

Final Fantasy X – July 19, 2001

FFVII was a breakout hit on the original PlayStation, and FFX aimed to duplicate that success on the PS2. While it wasn’t the first fully 3D JRPG, FFX’s production values were significantly higher than those of its contemporaries. Voice overs and custom animations were no longer limited to prerendered cinematics, and the overall fidelity was a clear step up.

It might not have been as drastic a transition as the series’ previous generational leap, but the sales and critical reception of FFX all seemed to indicate that it lived up to its hype. Consequently it received various remasters, and was the first mainline entry to get a direct sequel.

It was also the first Final Fantasy game that I gave up on when it deposited a net in my hands and told me to go catch some butterflies.

After a short and somber intro showcasing the game’s cast, the player takes control of Tidus, a professional athlete on his way to a sports match.

Following 10 minutes of fan-conversations and some very linear exploration, the event kicks off but is immediately interrupted by a huge monster attacking the city. A companion quickly joins up, and the first battle takes place. The combat is quite fast, with hasty animations and the old ATB system being replaced with one that instantly skips to the next combatant’s turn.

The intro combat sequence is quite interesting as the party faces enemies both in the front and back, with the rear enemies respawning if killed. By defeating the front ones, the party “moves forward” without exiting the battle scene. Eventually an easy boss fight takes place, and a save point is found right after.

Following some surreal cutscenes, the player is deposited in the first dungeon. The area is quite atmospheric, with the mystery of what just happened and where the protagonist finds himself squarely in the forefront. There are no immediate explanations, just monsters and a sense solitude. An item is found pretty quickly, and after some light puzzles and a level up, a human faction is encountered that speaks a foreign language (a rarity in JRPGs).

The encounter with the Al Bhed results in a lengthy tutorial on obtaining abilities, and yet another dungeon. The protagonist is eventually separated from the group and transported to a whole new location. Here the game proper begins, and after a lot of cutscenes, tutorials, and exploration, the first reusable rest spot and equipment are discovered.

However, it’s not quite enough to reach the next hub within 2 hours.

FTC: NA

Miscellaneous Points:

- Tidus is far from a silent protagonist, going so far as to narrate the game via as a series of flashbacks.

- The minimap works well in aiding exploration without showing too many details.

- There’s an extra option when swimming to dive, giving traversal mechanics a slightly different feel from other JRPGs.

- The worldbuilding in FFX is some of the best in any JRPG. The setting’s history, factions, religious customs, magical monsters, etc. are all logically intertwined and used to give motivation to both the protagonists and antagonists.

- Combat is quite fast and fluid as it isn’t entirely driven by a linear transition of states, e.g., the player can quickly select to attack a retreating enemy while it’s still in its leaping-back animation, chasing it right away instead of waiting for the target to return to a default state before the combat menu pops up.

- There are multiple levels to stealing from monsters — increasing in difficulty with each success — and overkilling targets drops more/rarer items.

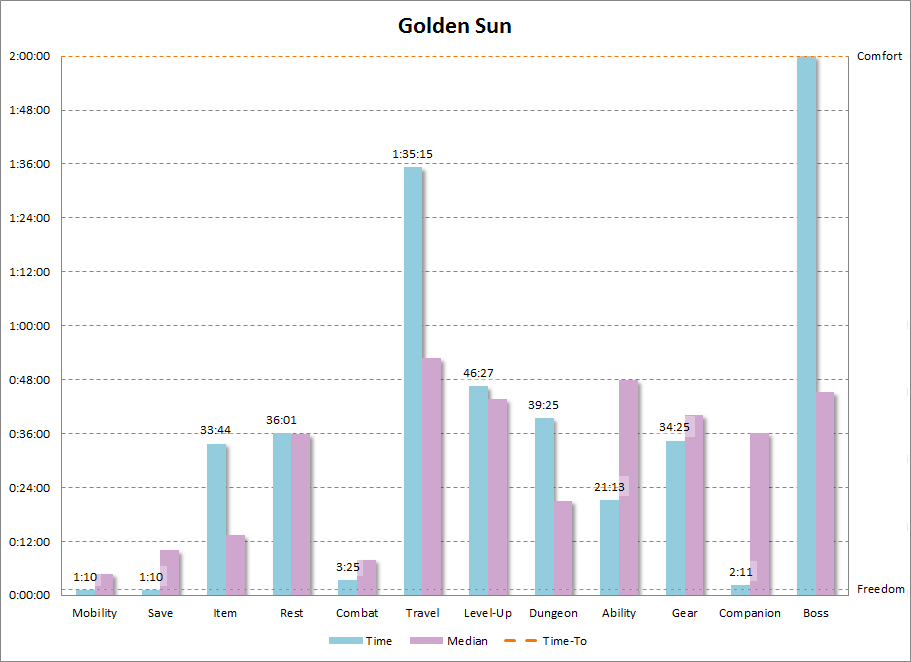

Golden Sun – August 1, 2001

Golden Sun served as something of a next-step JRPG for Pokemon fans. It was split into two titles on the Game Boy Advance, and received a sequel on Nintendo DS. Despite not selling a tremendous amount, the series gained a cult following that cherished its focus on puzzle dungeons.

Golden Sun starts off very quickly by making the introduction largely interactive. Saving can be done at any point from the main menu, and a companion joins up right before the first fight. However, the rest of opening slows down to an crawl due to the first instance (at least on these lists) of text-grind.

Just like in visual novels, all characters have a lot to say. They constantly repeat themselves, restate and confirm the obvious, and generally take a long time to say nothing.

The cramped text box doesn’t help matters, but what’s even worse are the constant dialogue interruptions. Characters not only take breaks to change poses, but also display floating emojis to reaffirm their emotional state. These elements really drag out the first half-hour, and the only new milestone during this time is obtaining a puzzle-related ability.

Eventually some shops open up providing items & equipment for purchase, and the first rest spot becomes available. The dungeon that follows isn’t too difficult, but random encounters are quite frequent and the combat has a halting flow. This is mainly due to a Dragon Quest like battle log where each message must be manually confirmed.

Just over an hour and a half into the game, the opening sequence finally ends. The party sets out on the overworld map, but this doesn’t leave enough time to encounter the first boss.

FTC: NA

Miscellaneous Points:

- The dungeons are very enjoyable, frequently going beyond simple switch puzzles and invoking unique abilities, e.g., growing climbable vines in the recesses of walls, freezing water so that it forms pillars of ice that can be jumped across, blowing away shrubs with a whirlwind to reveal secret passages, etc. These are sometimes usable in combat as well, making the game feel more like a cohesive whole.

- Puzzle-exploration is also present in towns, providing a steady stream of clever ability-interactions.

- When an enemy is defeated, other characters targeting that enemy don’t automatically select a new target. Instead, they somewhat annoyingly give up on their action and simply defend.

- Due to the lack of a backlight on the original Game Boy Advance, the game’s colour palette is quite bright and garish.

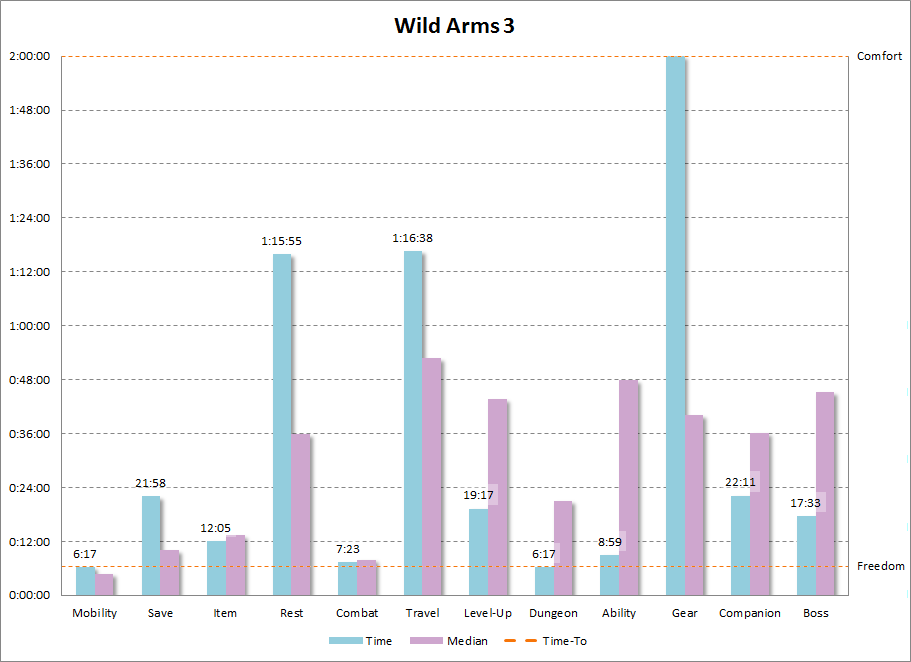

Wild Arms 3 – March 14, 2002

Despite its reputation for being a Western-themed series, Wild Arms always focused on magic, monsters, castles, mechs, and other common trappings of JRPGs. Out of all the games, Wild Arms 3 came closest to capturing the vibe of the Wild West, and is arguably the series’ standout entry.

A scripted sequence introduces something of a crisis aboard a train, with the four main characters facing each other in a standoff. This serves as a character select screen, with the option to play through the prologues in any order before the game proper begins.

Starting with the default character, a short cutscene plays before she’s ushered into the first dungeon. Combat takes place right away, and an ability is found shortly after to help with environmental puzzles. The first items is collected following some exploration, and within 10 minutes the first boss encounter takes place.

When the boss is defeated, a level up takes place and a save option is presented before moving on to the next character’s section. This pattern continues for all party members, which is why there’s a long delay before resting and overworld travel come in at around the 75 minute mark. The last dungeon also proves too lengthy to obtain the first gear upgrade before the 2 hour marks elapses.

FTC: NA

Miscellaneous Points:

- Loading a game plays a series of anime clips that don’t appear prior to the title screen or when starting a new game.

- Conversations allow the player to “ask” about any underlined topics with a separate button press, which is required to progress through some quests.

- Similarly to Lufia II, dungeon exploration revolves around traversal puzzles and the use of “tools” — abilities unique to each character that facilitate special map interactions.

- There’s an interesting system in place to manage random encounters. When a fight is imminent, an exclamation point appears over the lead character. The player can then choose to instantly enter the battle, or use a resource to skip it. While the exclamation point is active, the player can’t use tools, often forcing the player to deal with the situation one way or another. The skip-resource can be refilled by gathering it in dungeons or fighting battles, and skipping fights with underleveled enemies is free.

- The encounter rate itself varies greatly. I was convinced one room was free of enemies after spending a long time trying to figure out its puzzle, but a battle did eventually take place.

- There’s no escaping from fights once they begin. This actually led me to a walking-dead scenario after I wandered off to an area with high-level enemies and couldn’t make my way back.

- A POW bar fills up for every character as fights progress, fueling the use of their combat abilities. This ensures that players don’t just save up their MP for boss battles, and ensures that they can’t unload with their most devastating attacks right off the bat.

- Locations on the overworld map don’t appear until scanned with a button press. There are no other mechanics associated with this system, so the experience mostly comes across as repetitive trial-and-error.

- A vitality counter is drained to automatically heal characters after battles, retaining the feeling of attrition in dungeon exploration while eliminating healing busywork.

Baten Kaitos – December 5, 2003

Prior to their success with Xenoblade Chronicles, Monolith Soft aimed to shore up the GameCube’s scarcity of JRPGs with Baten Kaitos. Teaming up with tri-Crescendo, the two companies strayed a bit from tradition by basing the game’s combat on a card system.

The reception of Baten Kaitos was generally positive — it’s easily remembered as one of the console’s best JRPGs — but this did not result in tremendous sales numbers. A sequel was met with a similar reception, and the series was shelved soon after.

Following a 5 minute intro, control is given to the player in a small village with a save point, an item store, and a rest spot.

While beautiful looking, the scripting system shows its age with rigid, state-driven cutscenes. These require a fade-to-black intro and outro, resetting the position of all applicable NPCs and party members. Not only does this add an unnecessary delay, it also comes across as very awkward when the reset leaves all characters in the same spots.

Exiting the village leads to a miniaturized overworld map reminiscent of Chrono Cross. Here all key locations are close by and no random encounters take place. Entering the first dungeon is soon followed by combat, but the exploration is a much lengthier process. The areas aren’t sprawling, but a constant stream of new cards necessitates a fair amount of deck management.

After roughly 25 minutes in the dungeon, a boss battle takes place and a companion joins up after its defeat. From here things slow down considerably with more cutscenes and another dungeon area.

At the 75 minute mark, the first equipment upgrade is obtained, followed 10 minutes later by a brand new ability. The final milestone is hit in the second, much larger town where the mechanism for leveling up is finally unlocked.

FTC: 1:41:36

Miscellaneous Points:

- The biggest differentiating factor of Baten Kaitos is its card-based battle system, which comes with quite a few quirks:

- By default, all actions in combat — by both the party and the enemies — result in their own summary screen. This slow things down severely, and I turned it off to make it feel more like a typical JRPG.

- The timeframe for selecting defensive cards when being attacked is quite frustrating. There’s only a split second to parse which new cards have appeared since the offensive turn, which one of them are lit up and selectable as defensive cards, which cards should be dismissed in the hope of gaining a defensive card, and which defensive cards should be selected to most efficiently block incoming attacks. What’s worse, if a card is selected as the enemy begins its approach (not attack) animation, it’s often already too late to block the incoming onslaught.

-

- Deck reshuffling takes place after the 20th card is drawn, encouraging the use of powerful abilities instead of saving them for later.

-

Managing the party’s decks is a perpetual task. - Enemies tend to block the first attack, but not the second. However, saving the more powerful cards for the second attack can backfire since a new card comes in after the first one is used, meaning it’s possible the player could miss out on using two powerful attacks in a row to dispatch an enemy instead of damaging but not killing it.

- Regular playing-card numbering is present, facilitating Poker-style pairs and straights to increase potency. However, these happen incredibly rarely and have minimal impact on battles.

- Since cards never run out, it’s possible to save on consumables by using healing cards in-combat.

-

- The main way earn money is to sell photos of monsters taken in-battle with a camera card. Most items can only be sold for a handful of cash, but photos can fetch up to thousands of gold pieces.

- There’s not a lot of handholding in the game despite the unusual battle system. The difficulty scaling accommodates for this by not requiring intricate knowledge of all mechanics, and tutorial-dispensing NPCs periodically fill in the gaps.

- Blank cards can be used to absorb the essences of various environmental objects: fire, salt, feathers, etc. In a system akin to Chrono Cross’ quest-items, these “elements” can then be presented to NPCs, releasing them from the card to progress the story or complete side missions.

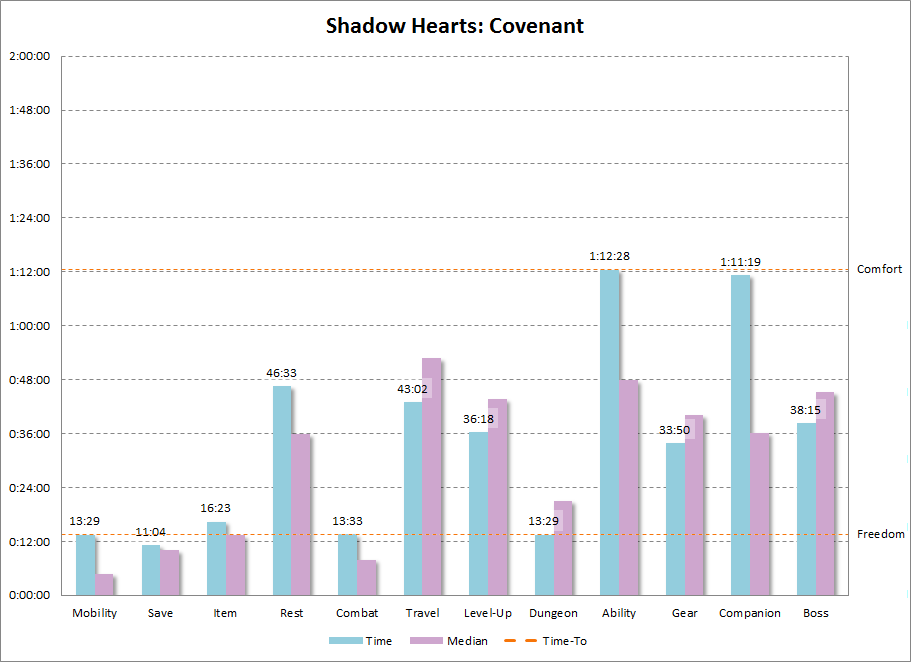

Shadow Hearts: Covenant – February 19, 2004

As a successor to Koudelka, Shadow Hearts took place in a fantastical version of our Earth just prior to World War 1. It combined wacky anime stylings with various occult elements of both the West and the East. Its own sequel, Shadow Hearts: Covenant, continued the tradition and picked up the story right after the first game ended.

Despite moderate sales, the PS2 series is a true cult-classic that’s lauded for its unique setting and combat mechanics.

The intro is fairly lengthy, actually allowing the player to save a few minutes before its conclusion. When the opening finally ends, the player is deposited in the first dungeon just before 15 minutes have elapsed.

Exploration is almost immediately followed by combat, and a few minutes later the first item is picked up. Tutorials accompany most random encounters during the next 20 minutes, which is somewhat understandable given the complexities of the battle system. The timed inputs of the Judgement Ring are used for many different action, and a combo system provides further options that are available from the get-go.

Hitting milestones picks up again during a 10 minute span where new gear is obtained, the first level-up takes place, the first boss is encountered, and the node-based overworld map is unlocked.

The second dungeon is of similar length to the first, but provides a rest spot early on. Roughly half an hour later, the party composition goes through a shake-up, and the final milestone is hit when a new ability is obtained.

FTC: 1:01:24

Miscellaneous Points:

- The Judgement Ring is a circle that pops up whenever an action is taken in combat and — in some cases — outside of it. A needle quickly moves around this circle’s circumference, and the player is meant to time button presses as it passes through hotspot-slices that take up portions of area. The execution is similar to that of rhythm games, and serves as the base for various mechanics:

- The further the needle moves into a hotspot, the more damaging the attack. The last sliver of a hotspot is red, representing a critical hit. This makes it advantageous to input at the last possible second, but risky as missing a hotspot will forego the hit.

- The number of hotspots corresponds to the number of possible hits, which, along with sizing, is character-dependent.

- Magic spells require a series of hotspots to be hit at any point while the needle overlaps them, with the last hotspot representing the spell’s power. However, if any of the preparation-hotspots are missed, the whole spell fails.

-

- Status effects can alter the input mechanic, making the ring shrink, hiding its hotspots, causing the needle to travel at different speeds, etc.

- Character customization allows individual tweaks to how the ring’s attributes by providing additional hotspots, growing their size and critical-hit range, appending debuffs like lowering evasion, etc.

- Wholsale changes to how the ring works are also possible, e.g., the gambler merges all hotspots into a single slice, but missing it means that no attacks will be launched.

- There’s something of a Lovecraftian sanity system in the game, which manifests as a berserk status if a fight goes on for too long. This is usually not a problem during regular battles, but can be a unique limitation when facing bosses.

- By never missing hotspots and fulfilling various other criteria, the player can obtain extra XP and items after a battle’s conclusion.

- Combos allow characters to launch enemies into the air, ground them, or push them back in order to open up weaknesses. Comboing requires all participating characters to be next to each other on the turns list, and their Judgement Ring inputs must be strung together with a link-input.

- It’s possible to combo with characters spread out on the timeline, but this relies on only starting the combo on the last character’s turn. Not only does it delay all outgoing damage, but the combo can still be interrupted and canceled. This itself can be countered by using MP to start an un-cancel-able combo, but that never seemed to be worth the cost.

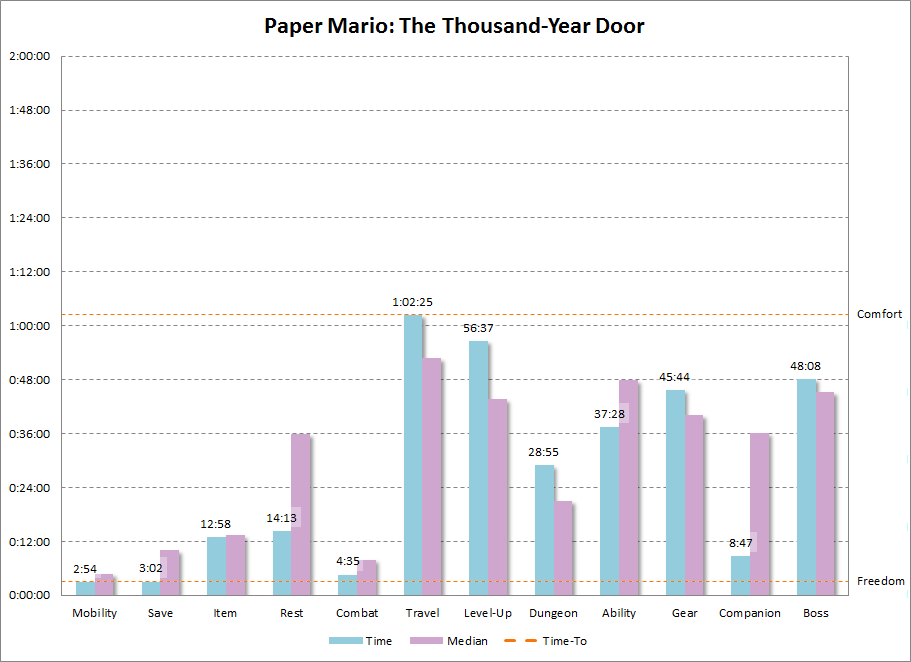

Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door – July 22, 2004

After the original Super Mario RPG, Nintendo and SquareSoft parted ways on rather unfriendly terms. This left the Nintendo 64 bereft of marquee JRPGs, leading Mario’s creators to develop their own quirky, papercraft-inspired sequel.

Nintendo continued this series with a GameCube sequel that improved on virtually all elements of the original. The Thousand-Year Door oozes charm, and stands the test of time better than perhaps any of its contemporaries.

After a quick, storybook-framed intro, the player is deposited in a seedy port town. A save point is visible in the distance, and just beyond it Mario gets himself into a rather comical scrap.

The character he rescues eventually joins up, and exploring the town quickly reveals an item shop and an inn. A series of thorough tutorials and cutscenes follow, but within the first half hour Mario finds himself in a dungeon.

The underground area is fairly small, but has a decent amount of side areas and interactive elements. Enemies are visible on the map and can be avoided, but due to input-mechanics, actual combat takes a fair amount of time. Thankfully defeated enemies don’t respawn while in the dungeon, making backtracking quick and easy.

A new ability must be obtained in order to proceed, which leads to the first equipment upgrade and boss fight. This doesn’t immediately result in a level-up, but that takes place right after reaching the next area. Once there, a linear path guides Mario to the second hub-town, hitting the final milestone just over an hour into the game.

FTC: 59:31

Miscellaneous Points:

- The entire game is presented as an interactive 3D diorama with lots of thematic transitions, e.g., stepping through the front door of a house causes its walls to fall down and reveal the inside area.

- Stage props and papercraft elements are commonly mixed in with traditional Super Mario elements. A switch block can make one of the wall facades peel off to reveal a hidden path, or bend it into the shape of a staircase that leads to a new location.

- Plentiful text effects make even simple conversations feel fun and bouncy. The font can shrink or grow, individual characters can shake violently or animate via offsets for a sing-song effect, icons and pictures can be used alongside the text, and the borders and colour scheme of the speech bubble can change based on who’s talking.

- All combat abilities have their own unique input mechanics, which are a lot more varied than Shadow Hearts’ unified Judgement Ring. Timed presses are required to keep jumping on enemies, the hammer smash has a windup requiring the control stick to be held left until a countdown finishes, an enemy scan requires proper timing to hit a hotspot, etc.

- Two different timed-presses are present for managing incoming damage, one lowering it and the other reflecting it back at the enemy. The second option is much riskier as it has a tiny time-window, but rewards expert play.

- Jumping on enemies in the field or hitting them with an ability grants a free turn to the attacker when the combat begins. What’s interesting is that the move the enemy was hit with is the same one launched when the fight begins, complete with an input-minigame.

- All battles are presented on a theatre stage, and the game leans heavily on this framing. Stage props can fall from the rafters and require extra block-inputs, while the audience itself can toss recovery items to foes or attack the player’s party (requiring yet another timed button press to mitigate the danger). The quantity of the audience also differs from fight to fight and affects the rate at which star points fill, fueling the party’s super-move bar.

- Enemies only give XP by default, but can sometimes drop coins when defeated. Occasionally they also leave behind consumable items, which can be seen being carried by the enemies prior to the fight.

- The way Mario acquires new abilities is through a “curse” by a presence that’s bitter about being trapped in a box. These encounters are quite humourous and come with a tutorial that has the malevolent being mocking Mario by providing helpful tips.

- In typical Metroid fashion, abilities can unlock new sections of previously visited locations. These areas are clearly signposted ahead of time, making it easy to remember unexplored routes when a new ability is obtained.

- Companions come with their own special abilities — usable both in combat and the field map — and all of these require their own input-minigame.

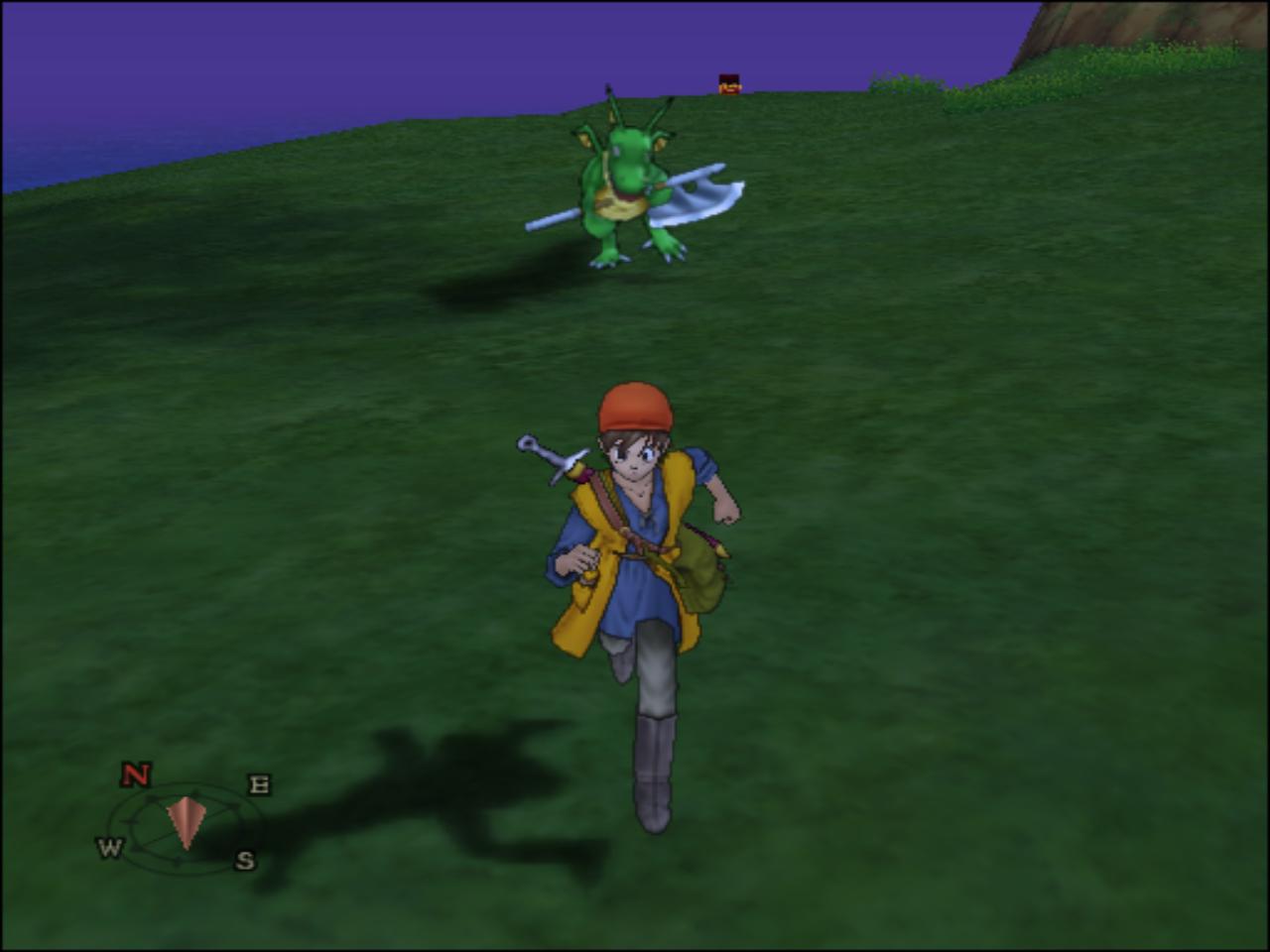

Dragon Quest VIII – November 27, 2004

Dragon Quest has historically been something of a comfort-JRPG, holding on to its conventions while being dragged kicking and screaming into each new console generation. Dragon Quest VIII felt like a lot of these holdovers were finally left behind — Dragon Warrior was no longer its title, voice acting was added, a fully 3D presentation was embraced, etc.

However, thematically the game was still firmly set in its roots. Instead of an epic quest, its narrative felt more like a fairy tale where the party adventured from town to town getting to know the inhabitants and helping them solve comparatively minor problems. This approach finally proved successful both in the East and the West, and Dragon Quest VIII went on to be lauded as a highlight of the series.

After a short 2 minute intro, the player is deposited in a small area and almost immediately enters combat. An item is discovered after the battle’s conclusion, and a cutscene has the protagonist’s companion officially join the party.

The group eventually arrives at the first town packed with colourful residents. A store provides a gear upgrade, and a fair amount of dialogue sequences take place to progress the story. After the final cutscene, an inn opens up and the city’s gates are unlocked.

A path to the first dungeon is evident from the get-go, but the overworld map is presented at the same scale as the town. This results in a lot of time spent exploring even if the random encounter rate isn’t overly high. This approach requires multiple trips back to town to restock and recover — gaining a level and the first ability along the way — and takes nearly an hour to complete.

The dungeon itself is finally ready for exploration at the 90 minute marks, and the final milestone comes only 15 minutes later with the first boss battle.

FTC: 1:45:47

Miscellaneous Points:

- Previous Dragon Warrior localizations experimented with accents and different speech patterns, but with actual voice acting and a clever script these flourishes really come to life in DQVIII.

- Leaving a bit of abstraction behind, lots of nifty animations have been implemented such as opening dressers and cabinets, leaping down wells, smashing pots, and flipping through books.

- Combat can be fairly tough, but enemies are on the cartoony side with many cute touches: cats randomly skip a turn by cleaning themselves, big-lipped critters can lick a party member and inflict the grossed-out status effect, dancing devils make characters catch the “dancing bug” forcing them to bust a move, etc.

- A combat log narrates the action, explaining exactly what is going on behind the scenes. Much like the visuals, this narration is quite whimsical and shows a lot more personality than typical CRPG combat logs.

- Unlike Dragon Quest VIII’s 3DS remake, most combat is done via random encounters. However, large enemies still roam the overworld map and can initiate battles. These aren’t bosses, but typically higher level monsters that pose a real danger when first encountered.

- Enemies tend to have a limited amount of MP and can only cast one or two spells before running out. When this happens, they continue attempting to cast spells, but fail and waste a turn. This makes the game feel fair and allows the player to exploit the behaviour by deprioritizing 0-MP targets.

- Leveling up eventually allows the player to manually distribute talent points into 3 specific weapon skills, unarmed fighting, or a character-specific ability. These decisions are not only important for long-term builds, but also make an impact in the short-term as damage numbers are so low that even an increase of 1 point can mean the difference between defeating an opponent in a single turn or dragging out the battle to at least two rounds.

- Humourous cutscenes frame a lot of the content, even in dungeons, e.g., a mole enemy will back away intimidated if you tell it you’re a tough fighter, or a boss will retreat behind his waterfall if you refuse to admit that you’re there to steal his MacGuffin.

Persona 4 – July 10, 2008

The Persona series started off as one of many MegaTen spinoffs, but developed its own identity over time. Persona 3 was the first entry in the series to really take off, combining the high school setting with new mainstays such as social links, a strict day-by-day timeline, non-combat attributes, snazzy UI, and a pop-y, earworm soundtrack.

Persona 4 ran with these changes and polished them up, segmenting the randomly generated dungeons into narrative and aesthetic wholes, giving full control of all party members, and switching up the setting to a rural Japanese town. It’s arguably a series favourite and received multiple spinoffs and upgrades, including a recent PC release.

It’s also the only game on this list that I’ve previously played to completion.

Persona is notorious for aping text-heavy visual novels, but this doesn’t take it completely outside the bounds of the 12 milestones. The multi-faceted opening that mixes anime and in-engine cutscenes ends just after 10 minutes, and the game then rapidly hits the mobility, save, rest, and combat milestones.

However, the railroading soon resumes, slowly introducing the setting and the game’s narrative hook. This ends at the 1 hour mark, with the party preparing to face the dangers ahead. Within 15 minutes, the first consumable is found, a level-up takes place, a boss is fought, and the first new ability is unlocked. This segment is still entirely scripted, though, with no free movement and all progression stitched together with cutscenes.

The real dungeon preparation takes place at the 100 minute mark, with gear upgrades and the first companion officially joining the party. 10 minutes later dungeon-exploration finally opens up, but this proves not quite enough time to unlock the final travel milestone via a town map.

FTC: NA

Miscellaneous Points:

- Mimicking visual novels, there’s an option to auto-progress through dialogue after an adequate delay or once a voice clip finishes playing. This works OK, but doesn’t flow very smoothly as there’s still a pause between individual text boxes. Animated emoticons similar to those of Golden Sun further slow things down and make conversations feel very lock-step.

- As with many MegaTen titles, the player is required to name the protagonist. This includes both a first name and a last name, and provides no default option.

- The protagonist possess various attributes that solely affect social interactions, which in turn power monster-fusing and some optional content. There’s a limited amount of chances to raise these stats, which make for interesting and meaningful choices.

- Progression is done along a strict timeline that lasts a couple of months, with each day offering numerous options for activities such as exploring a dungeon, hanging out with friends, or improving one’s attributes. It’s not quite a simulation, though, as each day in the game contains some scripted events that drive the narrative, and each month requires a single dungeon and its boss to be defeated.

- Much of the combat takes its cues from the MegaTen games with a similar spell list and the ability to gain extra turns by exploiting the enemies’ elemental weaknesses. This can also leave enemies defenseless for a round, and doing this to all opponents unlocks a group attack that costs no MP and targets all enemies.

Conclusion

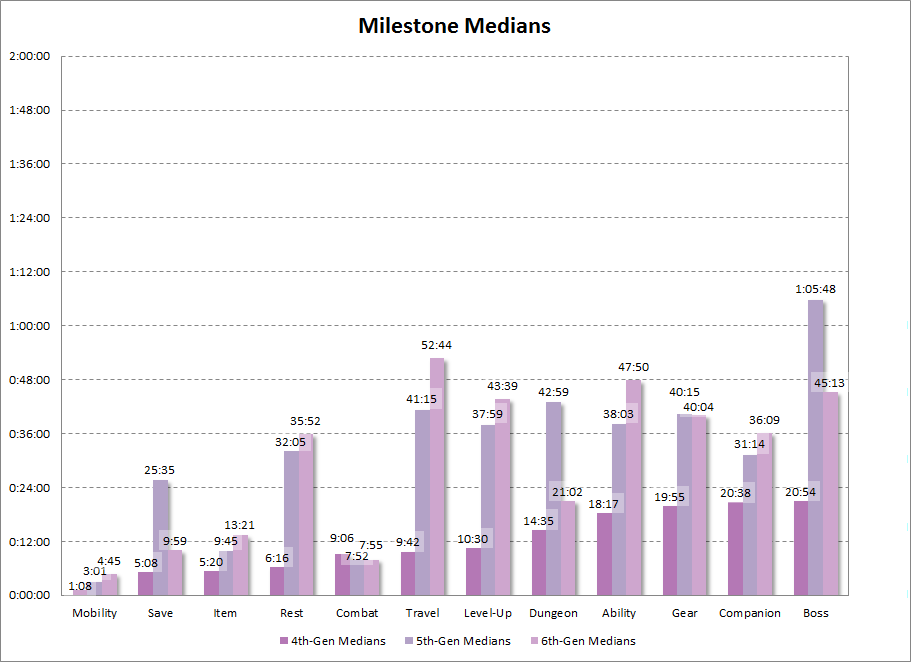

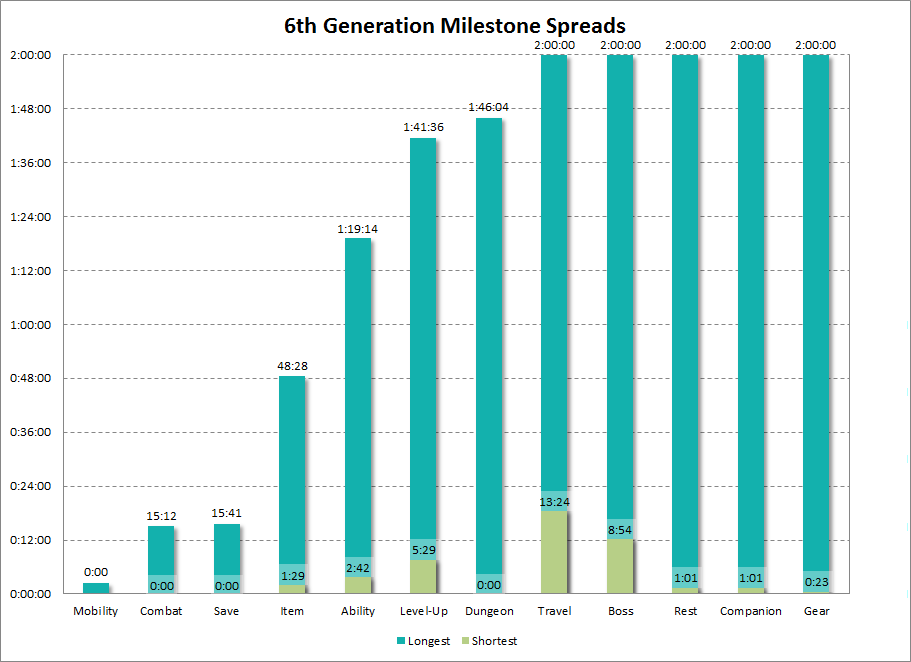

There was a general rise in 6th generation median times, but it wasn’t nearly as dramatic as the previous transition.

Out of the seven milestones that took longer to reach, each increased by roughly 10 minutes or less. Two other medians — combat and gear — also stayed at pretty much the same spot, only differing by a few seconds.

The remaining three milestones actually dropped, and these were fairly significant as each decrease was greater than any of the increases.

Saving happened 15 minutes earlier, perhaps looking to address frustrations from restarting lengthy intros. Both dungeons and boss battles also took place 20 minutes earlier, seemingly part of a concentrated effort to get players into the core experience much quicker. However, it’s worth pointing out that these sequences were still part of the onboarding process, with linear exploration and bosses that rarely posed the same threat as in earlier generations.

The milestone spreads generally increased as well, with five different ones falling outside the 2-hour limit (compared to just two in the 5th generation, and only one in the 4th). This indicated a larger divergence in JRPG pacing, although mobility, combat, and saving all shrunk down to become a universal core of the early-game.

Obtaining unique abilities also got slotted in earlier, which was indicative of more complex progression mechanisms. Leveling up actually leapfrogged the ability milestone, showing a clear desire to give the player something cool to play with early on in the experience.

I was actually surprised to see all milestones present in every game, although only four of them managed to hit FTC. Out of these, The Thousand-Year Door was the quickest to the mark, coming in at just under 1 hour despite its plentiful, hand-holding tutorials. However, the FTC metric became something of a misnomer as entirely new mechanics were being introduced 5-10 hours into various titles.

Combat typically stuck to the smaller cast of the previous generation — three party members, and a similar amount of foes. Long attack animations got curtailed, but combat wasn’t really faster due to additional meta mechanics. Keeping track of turns-lists, common resource pools, physical navigation of the battlefield, and completing input minigames all worked to extend the battles.

The combatants themselves also got more customizable and tended to stay in the party instead of departing for narrative reasons. This presented XP-distribution and character-progression issues, and the higher fidelity presentation made the “reserve squad” that much sillier to witness. Even when fighting in open fields, only the current party could attack the enemy forces. Other companions could tag-in, but if everyone on-screen died, the fight was over.

These types of suspension-of-disbelief problems became extremely common in the 6th generation. As JRPG visuals got less abstract, their mechanics became more so. This “systemization” became a big part of how the games were advertised, and convoluted gameplay ideas always seemed to trump narrative and worldbuilding concerns.

The upside of a willingness to experiment was that the games were more mechanically varied than I anticipated. There might not have been any titles quite as unique as Panzer Dragoon Saga, but Minstrel Song, Dragon Quarter, Mana Khemia, and various others prevented the genre from becoming trite.

What did leave a sour taste in my mouth were the character-driven stories.

Most narratives were incredibly juvenile and formulaic, endlessly regurgitating Shonen Jump tropes. There was rarely an attempt to appeal to a broader audience, or to even diversify within the existing one by taking cues from YA novels and other Western media. This rigidity left me feeling alienated and made me wonder — could JRPG storytelling ever move in a different direction?

Ahhhhhhhhhh Skies of Arcadia. They don’t make em like that anymore. Awesome sense of adventure.

so out of these which one was your favorite? Persona 4?

Overall, probably. Although that’s highly tainted by nostalgia. I also liked it despite its plethora of tropes as it was my entryway in to SMT. For a newcomer, the legacy of demons and their fusions, the Press Turn battle system, and Persona’s social gameplay along with its framing and setting were a breath of fresh air.

But in retrospect, I also appreciate Skies of Arcadia’s exuberant spirit, the elegant systems of Wild Arms 3, and the whimsical yet polished experience of The Thousand-Year Door.

I wonder myself more and more why I can’t finish JRPG anymore. I’ve played most of those games and JRPG was my first love <3. First of all congrats because your 3 parts article was clearly a labor of love, and you did an exceedingly thorough research. I feel it would have benefited from a synthesis of the 3 parts ? Also I found the data a bit inconclusive w/ regard to your initial introduction (= the fact that it was difficult for you to play JRPG anymore). Is inflating the TTF & TTC done on purpose ? In an hypercasual age where fortunes are made on making game you understand in 10 secondes, can long TTF/TTC explain the downfall or staleness of JRPG ? Are there company that try to curb the trend ? Anyway, thanks for the awesome read !

Thank you! My analysis leaned toward answering why I so quickly get turned off by modern JRPGs rather than why I can’t finish them, which the FTC metric aimed to showcase. In the very least, it catalogued that the games have been taking longer and longer to “get going,” and I added some more qualitative analyses such as the rigid, juvenile narratives to contribute to my overall falling out-of-love with the genre.

With that said, maybe I could’ve concluded with a bigger meta-view. My initial idea was to present how the TTF/TTC could’ve contributed to critical/commercial performances, and maybe do at least one more console generation, but ultimately I found that the genre was changing too much to keep going with my initial “model.” It was also quite time-consuming, so I’d like engage with some less demanding topics going forward, but I’m glad you enjoyed it!

I’m playing Final Fantasy X on my Switch for the first time, and I’m noticing the UI update compared to the PS2 original. One other issue I like is how teammates have very strict roles when it comes to fighting: Wakka hits flying targets, Tidus hits evasive enemies, Auron pierces armored foes, etc. That really helps simplify JRPG combat beyond “Make numbers really big before enemy numbers are too big”. I find that’s the biggest problem with modern JRPGs: Too many meaningless numbers and too much text to skip through.

(I also ignored the butterfly catching demo, haha!)

I think you summarized my issue with “This “systemization” became a big part of how the games were advertised, and convoluted gameplay ideas always seemed to trump narrative and worldbuilding concerns.” Lots of number crunching and repetitive “teenager uses the power of friendship and this big sword to kill god” storylines.

Minor typo in the Baiten Kaitos section: “Regular playing-card numbering is present, facilitating Poker-style pairs and straights to increase potency. However, these happen _icnredibly_ rarely and have minimal impact on battles.”

The simplicity of older games can certainly be alluring, although straight-forward puzzle combat can also become repetitive e.g., always using fire on ice enemies. FFX’s enemy-weaknesses aren’t quite as rigid, and the system itself has a fair amount of redundancy (that’s also incentivized via a desire to level up all characters by swapping them into battles):

Tidus is unavailable to attack a quick opponent with a high dodge? Target it with some black magic.

Lulu’s out of MP? Have Yuna cast some lower-level spells that still exploit the same weakness.

The mages are dead? Time for Rikku to dig up some offensive items.

These example are not necessarily the most efficient approaches, but they’re still viable and prevent the combat from feeling like a binary puzzle with just a single solution. Like you said, it’s not a complex system where the player needs to keep tracks of multiple resources, cooldowns, and various indicators common to modern JRPGs, but enjoyable enough within its scope.

Thanks for the typo catch as well; fixed now.

I’ve been a fan of JRPGs since around 2012, and it’s fascinating to look at how the genre has evolved over time into the games that I love today.

Especially interesting how TTF/TTC measurements vary so much as the games try new ways to mix up the kind of experiences they provide, like fleshing out individual locations and gameplay mechanics.

I used to be very impatient when I was younger, but eventually growing into VNs and RPGs helped me realize that a long stretch of *interesting* dialogue and story is better than a short *dull* moment.